Stop Groundwater Plan - Save $8 Billion by Majdi & Manaugh

Pitch

Systems thinking leads to a regional desalination plan to replace a narrowly conceived, costly and destructive groundwater pumping plan.

Description

Summary

Water scarcity is a huge problem that grows more serious every day because of unrelenting droughts caused by climate change. We propose a solution to a particular problem of water scarcity in Las Vegas, Nevada, that can serve as an example of two important guidelines that should be applied elsewhere in the U.S. and around the world:

- Reject short-term, local solutions that are unnecessarily costly and environmentally destructive.

- Look for regional, system-wide long-term solutions that are less costly, provide benefits to other water users in a region, and are environmentally responsible.

In this case, we propose rejection of an existing groundwater pumping plan for Las Vegas that (a) is very expensive ($15.45 billion), (b) would call for the biggest groundwater pumping project in the history of the United States, and (c) would cause severe long-term impact on water resources, threats to protected species, and permanent damage to the ecosystem.

Our alternative desalination plan, based on systems thinking, is much less expensive and more environmentally responsible. It involves offering Las Vegas a greater share of water from the Colorado River system in exchange for its providing supplies of desalinated water to Los Angeles. It could also save rate-payers and taxpayers in Nevada about $8 billion.

Many civic and environmental groups stand in opposition to the groundwater plan to bring water to Las Vegas from wells 263 miles away in eastern Nevada. Part of our proposal involves carrying out a public education and advocacy campaign to promote the desalination plan as a replacement for the groundwater plan.

Category of the action

Mitigation/Adaptation, Changing public attitudes about climate change

What actions do you propose?

Introduction

The category for this entry is "Adaptation/Mitigation, Changing public attitudes about climate change.” Therefore, proposed actions here include presenting the public and public officials with reasons to reject a highly flawed existing plan. The proposed actions also include presenting a better plan to replace the existing plan. The existing plan is called here the “Groundwater Plan,” and the replacement plan is called the “Desalination Plan.”

The Groundwater Plan

The Groundwater Plan (1) was first proposed in 1989 as a way of increasing water supply to Las Vegas. The plan currently involves transporting water by using a 263 mile-long pipeline originating in eastern Nevada. If completed, it would:

- Be the biggest groundwater pumping project ever built in the United States.

- Pump and transport up to 176,655 acre-feet of groundwater a year to Las Vegas from five valleys in eastern Nevada.

- Require construction of more than 4,000 acres of power lines, well pads and access roads.

The potential economic, social and environmental effects of this massive and unprecedented groundwater mining and export project are of great local, state, regional and national significance.

The Groundwater Plan has generated widespread opposition (2), including concerns expressed by White Pine County, Nevada; the Great Basin Water Network; the Sierra Club; the Central Nevada Regional Water Authority; the Confederated Tribes Of The Goshute Reservation; the Ely Shoshone Tribe; the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe; the Baker, Nevada Water And Sewer General Improvement District; Utah Physicians For A Healthy Environment; the Utah Rivers Council; Utah Audubon Council; the League Of Women Voters Of Salt Lake, Utah; the Center for Biological Diversity; the Army Corps of Engineers; and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Among the concerns expressed are:

- Very high cost to rate-payers and taxpayers. The Bureau of Land Management estimates the project will take 38 years for full completion and cost more than $15.45 billion.

- Pumping more groundwater than the target area contains.

- Violation of the National Environmental Policy Act by authorizing groundwater development by the Southern Nevada Water Authority's Clark, Lincoln, and White Pine Counties.

- Devastating hydrological, biological, agricultural, and socioeconomic impacts across vast areas of eastern Nevada and western Utah.

- Indirect harm to 130,000 acres of wildlife habitat, possibly causing several hundred springs to dry up and killing off several threatened species.

- Severe long-term impact on water resources, requiring additional analysis of impact on wetlands.

- Subsidence caused by heavy pumping of groundwater, where ground sinks into holes once filled by water.

- Eventual exhaustion of groundwater resources tapped by wells drilled because groundwater is not a renewable resource unless it is recharged at a rate at least equal to that of what is pumped out.

- Large amounts of greenhouse gases will be emitted from the natural gas power plant that supplies electricity for pumping and transporting groundwater.

The Desalination Plan

The Desalination Plan is an alternative to the Groundwater Plan. Its acceptance will require taking actions to change public attitudes about meeting the needs of Las Vegas in a cost-effective and environmentally responsible way. The plan will gain greater public exposure and acceptance if this entry enters into the final round of consideration in the CoLab contest.

If water shortages continue to develop the way scientists predict (3), Las Vegas will be forced to adopt some plan for mitigation. It will be important that the Desalination Plan should be well documented to be a robust and practical alternative to the flawed Groundwater Plan.

Desalination is a mature technology (4) that can be readily applied. At the start of 2012, approximately 16,000 desalination plants in more than 120 countries were operating at a total installed production capacity of 19 billion gallons per day (5). With desalination, we can tap into the world’s most abundant water resource—the ocean.

Instead of using a go-it-alone, Nevada-only approach as is the case with the Groundwater Plan, the Desalination Plan will benefit from a systems approach. Las Vegas will benefit economically by making use of significant resources in the present system whereby Las Vegas already gets 90% of its water. That present system is the system for allotting and controlling the use of Colorado River water, as administered by the Bureau of Reclamation of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

The economic viability of the Desalination Plan will be analyzed in detail to document how the plan can be implemented at a reasonable cost. That cost is presently estimated to be $7.4 billion for a robust system to insure against water shortages for Las Vegas; see "Costs" section below. That estimated cost is significantly lower than the estimated cost of the Groundwater Plan.

The $7.4 million figure includes a “miscellaneous costs” figure of $1 billion. Part of that money will be needed to identify and secure sites for the proposed desalination plant(s). Siting is always a difficult problem because many competing and inescapable concerns about effects on local residents, economic benefits versus disruptions, aesthetics, disruption of transportation corridors, environmental impacts, etc.

Desalination plants are already built on the Pacific Coast, and adding one or more new plants, as needed, will not be a daunting task to either build or pay for. A thorough study of the history of past siting processes will be part of what is carried out during the earliest parts of Stage 1. That will allow us to establish the feasibility of the Desalination Plan based on other efforts in the recent past. Already, 15 to 20 new desalination plants are planned for California by 2030 (6).

Desalination plants will be powered by renewable energy resources. The Desalination Plan will call for the addition to the system of one or more concentrating solar power (CSP) plants. Such plants are already operating successfully within a service area that includes Los Angeles and other coastal cities. Here, again, hard data and analysis will show that adding one or more CSP plants to the system would not be a daunting task to build or to pay for.

A possible location for a CSP facility would be near the present site of the Ivanpah CSP facility in the southern California Mojave Desert that already supplies power to southern California via grid connections – the same grid that already powers desalination plants on the California coast. The Department of the Interior is engaged in identifying the best locations for large renewable energy projects – close to transmission lines and having fewer threatened species than other locations. In California, government agencies and environmental groups are working to identify large tracts in the Mojave Desert suitable for solar plants (7).

If this entry earns a Climate CoLab cash prize, all proceeds will go toward achieving the goals of actions described in Stages 1, 2, and 3.

Stage 1

The authors’ submission of an entry in this CoLab contest constituted the earliest step of Stage 1 activity, presenting to the public the Desalination Plan as a feasible alternative to the Groundwater Plan.

Other steps in Stage 1 include the following:

- Develop detailed arguments in favor of the Desalination Plan over the Groundwater Plan. Those arguments will be refined in consultation with civic and environmental groups that already are opposed to the Groundwater Plan for the reasons that were listed above.

- Document how technological issues related to desalination and CSP projects in the U.S. and around the world have been addressed. All relevant problems in providing infrastructure to support desalination and CSP installations should be considered and a history of successful solutions documented.

- Document how siting issues, including costs, were successfully addressed in California in the siting of facilities like the Carlsbad desalination plant and the Ivanpah CSP plant.

- Form a Special Advisory Committee made up of experts from various agencies, institutions of higher learning, and professional organizations like the National Research Council and the American Water Works Association. This committee will be appointed and approved by the concerned parties to address the following areas of potential concern as they relate to the Desalination Plan: technical, economic, social, environmental, and legal and institutional.

- Request the Department of the Interior to facilitate extension of present activities to include consideration of how desalination of Pacific Ocean water could help overcome water scarcity problems in Nevada and other western states. The Department has recently reported (8) success in executing a cooperative agreement for a pilot project to conserve water for the Colorado River system. The agreement was signed on July 30, 2014, by the Department of the Interior and municipal water suppliers from Colorado, Arizona, Nevada, and California. That historic agreement demonstrates states’ willingness to work together to overcome water scarcity problems. Clearly, the new agreement should encompass consideration of actions like implementation of the Desalination Plan that would reduce loss of water by evaporation as it is transported from Lake Mead to Los Angeles. Not transporting some of the usual allotment going to Los Angeles would conserve some water that would otherwise be lost to evaporation as it is transported through various canals and reservoirs. Additionally, energy would be saved with not so much water being pumped over various mountain ranges that traverse the canal that brings Colorado River water to Los Angeles.

- Prepare an analysis of what it would take to amend relevant laws and agreements regarding the use of the Colorado River.

Stage 2

A campaign should be mounted to inform public officials and the public about the Desalination Plan and how it could serve the interests of all participants who depend on water from the Colorado River. The civic and environmental groups, mentioned above, that are in opposition to the Groundwater Plan would be natural allies in getting both official and public support for the Desalination Plan.

The campaign will present these arguments:

- It makes basic sense to seek other sources of water if the current source being relied on is becoming depleted because of the effects of drought.

- Desalination is already being implemented successfully in California as well as thousands of locations around the world.

- Pairing construction of a new desalination plant(s) with a new CSP plant would be an environmentally responsible way to augment the system of water allotment from the Colorado River.

- California will benefit economically from the construction and operation of the proposed desalination and CSP plants.

Stage 3

Actual building of the plants needed to implement the Desalination Plan will take several years. Even so, the full implementation of the plan should take many fewer years than the 38 years suggested as needed for the full implementation of the Groundwater Plan.

Who will take these actions?

Because strong opposition to the Groundwater Plan already exists among civic and environmental groups in Nevada, it will be important to contact those groups to enlist their support. Those groups, if they agree with the alternative plan, will take the plan to the wider public and to public officials. Officials will have good reason to consider the replacement plan as water scarcity becomes ever more threatening and the Groundwater Plan becomes mired in controversy and lengthy lawsuits. (2)

For Los Angeles to forego a portion of its allotment of Colorado River water in exchange for supplies of local desalinated water, it will be important for several stakeholder groups in California to understand that the Desalination Plan will provide a more reliable source of water to Los Angeles than it would otherwise have in an era of unrelenting drought. Those stakeholder groups include:

- Public citizens who are consumers of water, rate-payers, and taxpayers. They have strong interests in seeing that water supplies are clean, reliable, and affordable.

- Municipal water officials who will need to be assured supplies of desalinated water will enter their local water system so as not to disrupt ongoing service.

- Agricultural business interests who will need to understand that delivery of some desalinated water to municipal Los Angeles will not disrupt their ongoing access to Colorado River water.

- Industrial water users will need to understand that their access to water supplies will not be made less reliable or more costly.

Given the legal aspects of water rights, state legislatures and the federal government will have a role to play to guarantee a smooth and expeditious implementation of the Desalination Plan. The U.S. Department of the Interior may use the example of the Desalination Plan in recommending similar plans in other regions where cost-effective and environmentally responsible solutions to water scarcity are needed.

Where will these actions be taken?

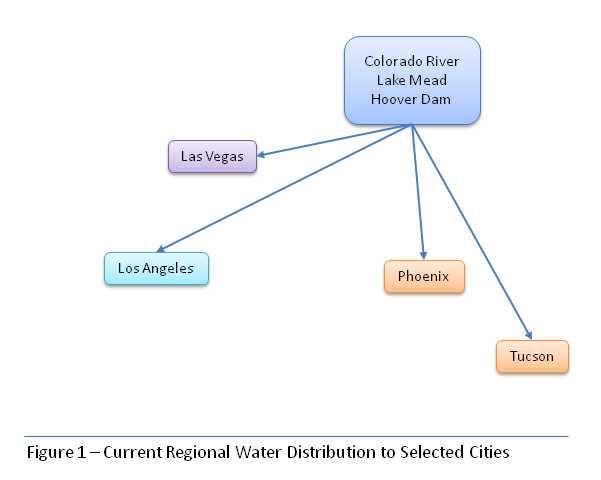

Figure 1 schematically shows the existing system for distributing water from the lower section of the Colorado River to selected cities in Nevada, California, and Arizona. System components include:

- Hoover Dam that dams the Colorado River to form Lake Mead reservoir.

- Population centers of Las Vegas, Tucson, Phoenix, and Los Angeles that receive water from Lake Mead. Allocations are monitored and controlled by the Bureau of Reclamation of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Lines that represent existing infrastructure of pipes, canals, siphons, reservoirs, and aqueducts that link Lake Mead to population centers.

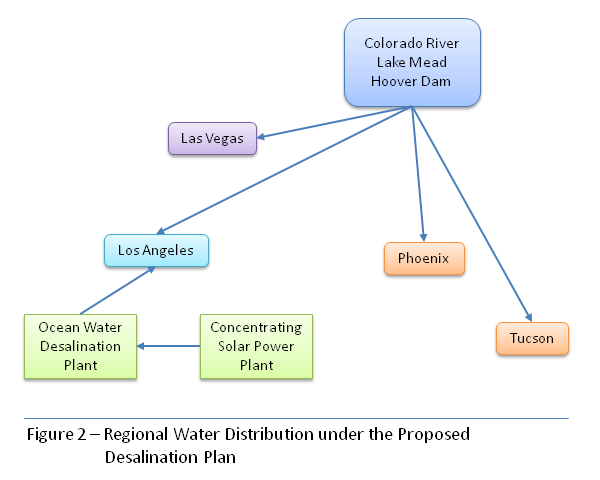

Figure 2 shows the same components as Figure 1 with the addition of:

- A desalination plant on the Pacific Ocean coast that is proposed to augment water supply to Los Angeles.

- Located in desert areas of California, a concentrating solar power plant is proposed to supply power to the desalination plant.

Supplying desalinated water to Los Angeles will allow a portion of the water allotted from the Colorado River to Los Angeles to be allotted to Las Vegas and, possibly, also to Tucson and Phoenix. Los Angeles will be compensated for a lower allotment by getting a reliable supply of desalinated water.

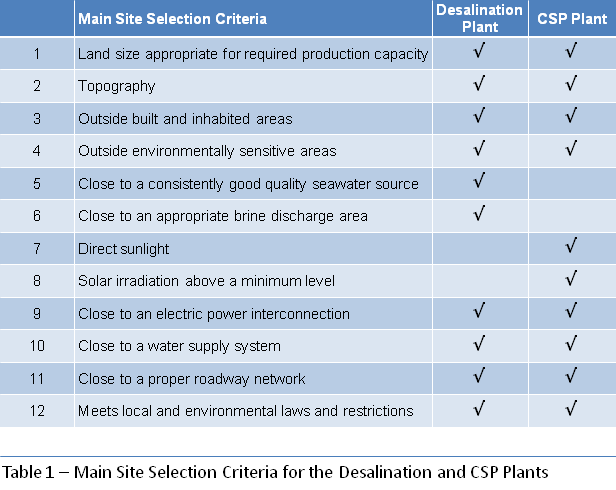

Acceptance of the Desalination Plan will be increased if stakeholders feel confident siting of desalination and CSP plants will be technically feasible, economically beneficial to chosen locales, and environmentally and socially acceptable. Sites will be determined by assessing multiple criteria, some of which apply to both types of plant. Table 1 shows main selection criteria that can be used to produce an initial list of site candidates (9,10).

A cost-effective method for candidate site identification uses geographic information systems (GIS), followed by field visits. A GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis (GIS-MCDA) could enhance confidence in the outcome of the selection process. (11,12)

What are other key benefits?

If the Climate CoLab judges find this entry worthy, stakeholders in Nevada will take notice and be encouraged to seriously question the advisability of adopting the Nevada-only Groundwater Plan – a plan that wastes billions of dollars on a project that is environmentally destructive and will eventually fail when groundwater resources become depleted.

By contrast, the Desalination Plan makes cost-effective and environmentally responsible use of an existing system. Additional water resources from desalination will make Los Angeles’ water supply less threatened by on-going drought.

Lessons learned from using systems thinking and regional cooperation could benefit Tucson, Phoenix and other cities around the world.

Combining use of power from renewable energy with desalination helps break a vicious cycle of negative environmental impact from using power derived from burning fossil fuels – a practice that contributed to the current water stress in the first place.

What are the proposal’s costs?

Advocating for the Desalination Plan as a replacement for the existing plan will cost a relatively small amount in Stage 1 and Stage 2, when details of the plan will be disseminated to stakeholders in Nevada, California, Arizona, and Washington, DC. Whatever costs might be incurred for Stages 1 and 2 for public education and advocacy would only be about the size of a rounding error for costs associated with Stage 3, implementing the Desalination Plan.

Stage 3 estimates are based on costs known for existing desalination plants (13) and existing CSP plants (14), as follow:

- $4 billion - Desalination plant(s) capable of producing a total of 200 million gallons of water per day.

- $2.4 billion - CSP plant(s) capable of providing a total of 3 million kWh per day, sufficient to power the desalination plant(s).

- $1 billion - Miscellaneous costs.

The total cost of $7.4 billion for the Desalination Plan is less than half of the cost of the Groundwater Plan.

Time line

Short Term

Stage 1 of advocating for the Desalination Plan started today with the submission of this entry in the Climate CoLab contest. Assuming some favorable feedback from judges, Stage 1 will continue for the next several months as we refine our proposal to replace the Groundwater Plan. Stage 2 will commence before the end of 2014, when we start to contact stakeholders in Nevada, California, Arizona, and Washington, DC. Stage 2 will continue until either construction is firmly underway on the Groundwater Plan, or it has been firmly rejected in favor of the Desalination Plan.

Medium Term and Long Term

Stage 3 will commence with the beginning of construction and will continue until the Desalination Plan is fully operational.

Related proposals

Adaptation to Climate Change

Improve Resilience through decentralising constructed wetlands for sewage

Global Plan

Strategically Transitioning To Global Adaptation!

References

- 1. Southern Nevada Water Authority. Clark, Lincoln, and White Pine Counties Groundwater Development Project Conceptual Plan of Development, November 2012, retrieved from the Internet 7/19/2014 at http://www.snwa.com/assets/pdf/ws_gdp_copd.pdf.

- 2. R. Kearn, Giant Nevada water transfer for Las Vegas under fire. CourthouseNews Service, retrieved from the Internet 7/19/2014 at http://www.courthousenews.com/2014/02/18/65413.htm.

- 3. K. Thompson, Last straw: How the fortunes of Las Vegas will rise or fall with Lake Mead. Popular Science, retrieved from the Internet 7/19/2014 at http://www.popsci.com/article/science/last-straw-how-fortunes-las-vegas-will-rise-or-fall-lake-mead.

- 4. Desalination. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, retrieved from the Internet 7/19/2014 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desalination.

- 5. J. Pankratz, IDA Desalination Yearbook 2011-2012, for Global Water Intelligence (Media Analytics, Ltd. Publishers, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2011).

- 6. N. Voutchkov, Advances and challenges of seawater desalination in California, Proceedings of the IDA world congress on desalination and water reuse (Gran Canaria, 2007).

- 7. Largest Solar Plant in the World Goes Through Last Test Before Opening, retrieved from the Internet 8/9/2014 at http://science.kqed.org/quest/video/largest-solar-plant-in-the-world-goes-through-last-test-before-opening/.

- 8. Commissioner’s Office, U.S. Department of the Interior and Western municipal water suppliers reach landmark collaborative agreement, retrieved from the Internet 8/9/2014 at http://www.usbr.gov/newsroom/newsrelease/detail.cfm?RecordID=47587.

- 9. N. Tsiourtis, Criteria and procedure for selecting a site for a desalination plant, Desalination, Volume 221, pp. 114-125 (Elsevier, 2008).

- 10. Fong and J. Tippett, Eds., Project Development in the Solar Industry, (Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, Florida, 2013).

- 11. A. Olufemi, et al, Adapting a GIS-based multicriteria decision analysis approach for evaluating new power generating sites, Applied Energy, Volume 96, pp. 292-301 (Elsevier, 2012).

- 12. E. Grubert, et al, Where does solar-aided seawater desalination make sense? A method for identifying sustainable sites, Desalination, Volume 339, pp. 10-17 (Elsevier, 2014).

- 13. N. Rott, The search for drinking water in California has led to the ocean. National Public Radio, retrieved from the Internet 7/19/2014 at http://www.npr.org/2014/02/26/281984555/the-search-for-drinking-water-in-california-has-led-to-the-ocean.

- 14. Ivanpah solar power facility. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia, retrieved from the Internet 7/19/2014 at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivanpah_Solar_Power_Facility.